Wanted: Big Waves

![[Back to MidWeek]](mwlogo.gif) Midweek 10/29/97

Midweek 10/29/97

|

Sunset Beach at the end of September is just waking up from its summer slumber. For months the camel-colored

sand has been adorned with young babes and dudes, clad in little more than

their exotic Oakley sunglasses and the latest fashions in bikinis and boardshorts.

The water, after all, has been warm, languid, crystal clear and flat-perfect for swimming or catching a 1- to 2-footer with a boogie board. What better place in all of Hawai`i, in all the world for that matter, to hang out, beat the heat and, above all, look really cool? Except for a half a dozen tourists lying on beach towels that still have their price tags on them, everyone who makes this scene in September knows that days like this are numbered. The winter season is approaching. The ocean is starting to wake up, yawning itself awake with storms that roll in from the far reaches of the Pacific. And storms, as we all know, mean waves -- big ones. Within a month, give or take a week or two, the long points, breaks and tubes that make up the surf along Oahu's North Shore will reach 10, 12, even 15 feet. And by December, Neptune willing, the backsides of these monster waves will rise 20 feet or more in the air as they lead the ocean's strike force against the shoreline. If you luck out and find somewhere to abandon your car along the stretch of Kamehameha Highway from Sunset to Banzai, you'll have a chance to witness just how spectacular, effortless, almost indifferent Mother Nature's power can be.

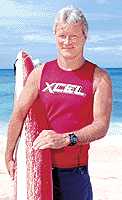

No one appreciates this incredible display more than Randy Rarick. To put things in perspective, the Triple Crown is generally recognized as the most prestigious surfing event in the world. The professional tour, in fact, builds to a climax and ends with the Triple Crown, which features three of the most prominent surfing contests the sport has to offer -- the Hawaiian Pro (now called the OP Pro Surfing Championship) at Haleiwa's Ali'i Beach, the World Cup of Surfing at Sunset Beach and the Pipe Masters at Banzai Pipeline. Now in its 27th year, the Pipe Masters is the longest-running professional surfing contest in the United States -- the surfing world's most prestigious individual contest. In short, the Triple Crown of Surfing is a huge event. It is estimated that it now reaches more than 300 million people around the world each year from domestic and international television broadcasts, satellite feeds, radio, print, home video and Internet sites. We're talking big money here, with big sponsors and big international interest. As the Triple Crown's executive director, you better believe Rarick appreciates a healthy winter swell. To put it another way, if Mother Nature fails to stage her show from mid-November to mid-December, it's his ass. Or, at the very least, he'll be treated like one. "People have actually blamed me for no surf!" he exclaims, sitting under an umbrella on Sunset Beach, 50 yards from the house he has lived in since 1975. "Remember 1994? We called it the 'Year of the Big Flat.' It was terrible. We were lucky to get 1 to 2 feet. "Fortunately, 1995 was great. It was one of our best events ever. think we'll have good waves this year, too. There's an El Nino condition right now, and that means there'll be more storms." As he sits in the sand and talks, Rarick pans the 2-foot surf through a pair of Maui Jim's. At 48, he is graying but fit, testament to the fact that he still surfs every day, though he retired from competitive surfing in 1977. In the late '60s and early '70s, he was a world-class surfer, repeatedly reaching the semifinals in many of the big surfing contests around the world. "I considered myself a journeyman, actually," he says matter-of-factly. "I was always up there, but always missing the elusive gold ring." Born in Seattle, Rarick's parents relocated to Hawai`i in the late '50s, when he was 5. He grew up in Kaimuki before the family moved to Niu Valley, where he used to surf. He actually named a surf spot near Niu Valley, which is still called "Toes Reef" today. He said the name came to him when he saw a friend hanging five over the front of the board. Rabbet Kekai taught me how to surf in Waikiki when I was 10," he says. "That was about 1960. Then in 1962, I was a model Boy Scout who had perfect attendance at our meetings. One day a surf movie came to town, you know, one of those documentaries that was only going to be here for one day. "It was a big decision to make! But I ended up going to the movie, and that pretty much was a turning point for me. Surfing has been my life ever since." He wasn't kidding, either. He started hanging out at surf shops and got his first job repairing surfboards when he was 14. Working after school and weekends, he made $125 a month, good money for a kid in those days. "I was what was called a 'gremmie,'" he says. "I learned a lot about boards, though, and I became a surfboard shaper." Rarick also became a very good surfer, winning the Hawai`i state championship as a junior in high school. As soon as he graduated, he traveled to Australia where he attended Sydney Tech (studying accounting and commercial law), surfed and learned the finer points of shaping boards. When he returned to Hawai`i in 1969, he opened his own surf shop, pulling the Dewey Webber dealership out from under his former employer. "The summer of '69 was a great year for me," he recalls. "I was young (19), had my own business and I was still surfing the pro circuit. I was on top of the world." He also was naive, burning the candle at both ends. Soon he found himself $25,000 in debt. The bottom fell out, and a wave of reality came crashing down on him. Wipeout! "It was just naive mismanagement," he shrugs. "I went from a high-rolling surfer and surf shop owner to a groveling night-shift worker, living in a $75-a-month flophouse with a bunch of old men." Shaping boards by day, working as a fiberglass sprayer at Pearl Harbor at night, he set about working off his debt. Meanwhile, he was starting to peak as a surfer, being picked for the World Team representing Hawai`i in Australia, and then catching the eye of the growing surfing community in South Africa. "They sent me a ticket -- all-expenses-paid -- to come to South Africa," Rarick says. "It was like a gift from heaven. I worked super-hard day and night to build up a stockpile of boards so I'd still have a job when I got back. When I left for South Africa, I had $50 in my pocket." Still, he managed to tour South Africa from one end to another, making it to the semifinals at a big contest held at Jeffrey's Bay. Afterward, he returned to Hawai`i and worked another year to pay his debts and save some money. In 1973, he sold everything he owned and went back to South Africa. "I bought a land rover, thinking I'd only be gone six months -- I ended up being gone for two years," he says, smiling. "I traveled from South Africa along the entire coast of West Africa, surfing places that had never been surfed before. Then I went from Europe and surfed anything that looked like a rideable wave." In a recent article in SURFER Magazine, Rarick is featured as having surfed in more countries than anyone on Earth (more than 60 different countries). He is quoted as describing the Congo thusly: "Except for the dead body floating down the river, this West African country is the kind of place you want to see at least once." As for Yugoslavia, he said: "Another of those strange surfs when you least expect it, in probably one of the most beautiful places I've ever seen." But Rarick longed to get back to South Africa, eventually returning for another six months. He then went to Brazil and the Carribean, island-hopping and surfing everywhere he could before re-entering the United States through Miami. Rarick was beginning to gain an international reputation, both as a surfer and as a board shaper. When he got back to Hawai`i, he organized the first American professional surfing tour to South Africa, which just happened to coincide with the plans of another hot young surfer named Fred Hemmings.

By 1975, Rarick and Hemmings, who in 1968 won the world championship in Puerto Rico, had pooled their expertise, created a rating system and put together the first professional world tour of surfing. The four big surfing meccas -- Hawai`i, Australia, South Africa and California -- suddenly became the sites for a new professional sport that was starting to gain international attention and legitimacy. Australia, however, honed in on the opportunity first, dominating and administering the professional tour until 1983. "So Fred, in his wisdom, decided we needed to bring surfing back to Hawai`i," Rarick recalls. "He said we needed a title for the winter tournament held each year in Hawai`i. "At that time, this included the Duke Surf Classic, which later became the Hawaiian Pro, the World Cup of Surfing and the Pipe Masters. What we wanted to do was recognize the best surfers in the best waves in the world and return the focus of the surfing world to Hawai`i, where it belonged." Thus, the Triple Crown of Surfing. Of course, Hemmings then decided to enter politics in 1988 (eventually making a run for governor) and sold his rights to the event to businessman Fred Williamson. Williamson was not a surf guy, so he kept Rarick on to run the event. And when ownership changed hands again last August -- purchased by Van's Shoes from the Mainland -- Rarick received a raise and even more responsibility, including a staff of 35. "What's good about Vans Shoes is we're going to be able to draw more sponsors now," Rarick claims. "They bring a lot to the table through their contacts in the sports attire industry. "I'm pretty stoked. We've bumped up the prize money for women surfers. And I'm proud to say that we've increased the overall prize money tenfold since 1983. Back then it was a total of $30,000. Today, it's over $350,000." While helping the sports apparel industry to become a $5 billion industry, surfing itself has had its financial ups and downs. Rarick says most people don't realize that the sport doesn't have a gate. Because the beaches are open, there's no way to recapture investments by charging an admission to these contests, and that makes sponsorships critical. "It's usually tied to the economy," he explains. "In the early '90s, we were eating it. But things have turned around." |